Sita Sings the Blues is an animated feature written, directed, and animated by Nina Paley. Thanks to its Creative Commons license, you can watch it in its entirety on YouTube. It tells the story of Sita, a central figure of a Hindu epic, and parallels it with the story of Paley’s divorce. It seems to be a love it or hate it movie. It’s weird in a lot of ways that are either charming or tacky, depending on your taste. If you’d like a sample of Sita, clicking on the screenshots will take you to that scene in the movie.

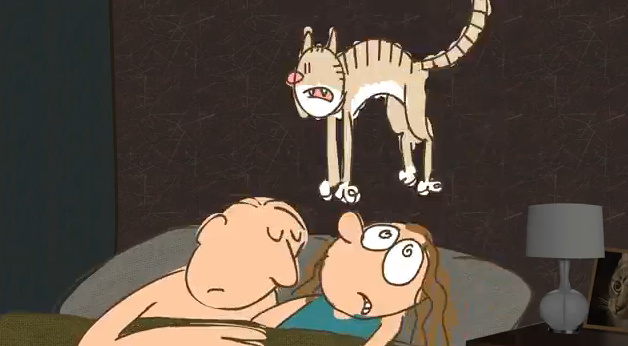

Paley uses several different animation styles throughout the film to create visual distinction between the stories. Her own story is drawn in a loose, sketched style that appears to be her signature.

Sita’s story is told three ways: in a fairly traditional drama, in improvised commentary by a group of people who grew up with the story, and in musical numbers. The drama, in which Sita, Rama, and the rest have dialog and interact directly with each other, is portrayed in what looks like traditional 18th century Rajput art (yes, I’m linking to Wikipedia for this one; remember, this is just an overview). They look like Paley cut them out of a textbook — which fits the straightforward narrative style — and is moving them around like paper dolls.

Contrary to what one might expect, the modern Indian commentators are animated as shadow puppets. This is what first reminded me of Sita in our discussion of Reiniger. More on that in a later post. The paper dolls reappear here with over-the-top comedic manipulation, almost like graffiti. The doodles look like they were done with cut-paste and the paint brush tool in MS Paint, which heightens the comedic effect and the irreverent tone.

The musical numbers are easily my favorite version of the story. You’ll notice that Annette Hanshaw is billed as the star in the opening credits. Hanshaw was a jazz-pop singer in the later half of the 1920s. (Fun fact: she performed some songs as proto-Betty Boop Helen Kane impersonations, including “I Wanna Be Loved By You” and this song that I dare you to listen to all the way through. The rest of her repertoire is much better.) In the musical scenes, Sita lip syncs to Hanshaw’s songs. These scenes are even more cartoon-y than Paley’s modern story. It’s all bright colors, bubble bodies, and vector animation. I love it.

And then there’s Sita’s fire. Spurned by her husband, Sita throws herself onto a funeral pyre as a show of her anguish and worthiness of Rama’s love. In the movie, this scene is portrayed twice. The first time is in a musical number with bobbing palm trees, dancing monkey-men, and a char-broiled Sita smiling and singing in flames. The second time is after Paley is dumped by her husband. Reena Shah, who provided the speaking voice for Sita, performs an original dance, which Paley rotoscopes and puts on a vivid, erratic background. It’s honestly beyond description. If you watch nothing else of this movie, watch this scene. (Heads up, it features bright, rapidly flashing images.)

Sita provides so much material for discussion that I could probably write the rest of the semester’s blog posts on this one movie. I’ll only do three: this introduction to the movie, a quick interpretation of it, and an analysis of its influences.

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Sita Sings the Blues: Interpretation | History of Animation Blog